The Powhatan Indians

At the time English colonists arrived in the spring of 1607, coastal Virginia was inhabited by the Powhatan Indians, an Algonquian-speaking people. The Powhatans were comprised of 30-some tribal groups, with a total population of about 14,000, under the control of Wahunsonacock, sometimes called “Powhatan.”

At the time English colonists arrived in the spring of 1607, coastal Virginia was inhabited by the Powhatan Indians, an Algonquian-speaking people. The Powhatans were comprised of 30-some tribal groups, with a total population of about 14,000, under the control of Wahunsonacock, sometimes called “Powhatan.”

The Powhatans lived in towns with houses built of sapling frames covered by reed mats or bark. Villages within the same area belonged to one tribe. Each tribe had its own “werowance” or chief, who was subject to Wahunsonacock. Although the chiefs were usually men, they inherited their positions of power through the female side of the family.

Agricultural products – corn, beans and squash – contributed about half of the Powhatan diet. Men hunted deer and fished, while women farmed and gathered wild plant foods. Women prepared foods and made clothes from deerskins. Tools and equipment were made from stone, bone and wood.

The Powhatans participated in an extensive trade network with Indian groups within and outside the chiefdom. With the English, the Powhatans traded foodstuffs and furs in exchange for metal tools, European copper, European glass beads, and trinkets.

In a ranked society of rulers, great warriors, priests and commoners, status was determined by achievement, often in warfare, and by the inheritance of luxury goods like copper, shell beads and furs. Those of higher status had larger homes, more wives and elaborate dress. The Powhatans worshipped a hierarchy of gods and spirits. They offered gifts to Oke to prevent him from sending them harm. Ahone was the creator and giver of good things.

As English settlement spread in Virginia during the 1600s, the Powhatans were forced to move inland away from the fertile river valleys that had long been their home. As their territory dwindled, so did the Indian population, falling victim to English diseases, food shortages and warfare. The Powhatan people persisted, however, adopting new lifestyles while maintaining their cultural pride and leaving a legacy for today, through their descendants still living in Virginia.

Pocahontas

The renowned Indian maiden who befriended English colonists in Virginia in the early 1600s has been immortalized in art, song and story.

The renowned Indian maiden who befriended English colonists in Virginia in the early 1600s has been immortalized in art, song and story.

Born about 1596, Pocahontas was the daughter of Powhatan, chief of over 30 tribes in coastal Virginia. Pocahontas was a nickname meaning “playful one.” Her formal names were Amonute and Matoaka. Pocahontas was Powhatan’s “most deare and wel-beloved daughter,” according to Captain John Smith, an English colonial leader who wrote extensively about his experiences in Virginia. Powhatan had numerous wives, and Pocahontas had many half-brothers and half-sisters. Her mother’s name is not mentioned by any 17th-century writers.

As a child, Pocahontas probably helped her mother with daily chores, learning what was expected of her as a woman in Powhatan society. Even the daughter of a chief would be required to work when she reached maturity.

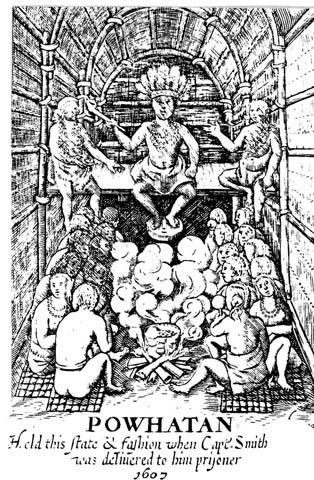

In late 1607 Pocahontas, then about age 11, met John Smith in an event he described years later. Smith wrote that he had been captured by Indians and brought before Powhatan at Werowocomoco, the chief’s capital town on the York River. After the Indians gave Smith a feast, they laid his head on two stones as if to “beate out his braines,” when Pocahontas “got his head in her armes, and laid her owne upon his to save him from death.”

Some scholars today believe the incident was a ritual in which Powhatan sought to assert his sovereignty over Smith and the English in Virginia. In 1608 Pocahontas assisted in taking food to the English settlement at Jamestown to persuade Smith to free some Indian prisoners. The following year, according to Smith, she warned him of an Indian plot to take his life.

Smith left Virginia in 1609, and Pocahontas was told by other colonists that he was dead. Sometime later, she married an Indian named Kocoum. In 1613, while searching for corn to feed hungry colonists, Samuel Argall found her in the Virginia Indian town of the Patawomekes in the northern part of the Powhatan chiefdom and kidnapped her for ransom. Powhatan waited three months after learning of his daughter’s capture to return seven English prisoners and some stolen guns. He refused other demands, however, and relinquished his daughter to the English, agreeing to a tenuous peace.

Smith left Virginia in 1609, and Pocahontas was told by other colonists that he was dead. Sometime later, she married an Indian named Kocoum. In 1613, while searching for corn to feed hungry colonists, Samuel Argall found her in the Virginia Indian town of the Patawomekes in the northern part of the Powhatan chiefdom and kidnapped her for ransom. Powhatan waited three months after learning of his daughter’s capture to return seven English prisoners and some stolen guns. He refused other demands, however, and relinquished his daughter to the English, agreeing to a tenuous peace.

Thereafter, Pocahontas lived among the settlers. The Reverend Alexander Whitaker, living up the James River near Henrico (Henricus), taught her Christian principles, and she learned to act and dress like an English woman. In 1614 she was baptized and given the name Rebecca. Soon after her conversion, Pocahontas married John Rolfe, a planter who had introduced tobacco as a cash crop in the Virginia colony.

In 1616 the Rolfes and their young son Thomas traveled to England to help recruit new settlers for Virginia. While there, Pocahontas had a brief meeting with John Smith, whom she had not known was alive, and told him that she would be “for ever and ever your Countrieman.” As the Rolfes began their return trip to Virginia, Pocahontas became ill and died at Gravesend, England, in March 1617. John Rolfe sailed for Virginia, where he had been appointed secretary of the colony, but left Thomas in England with relatives. Thomas Rolfe returned to Virginia in the 1630s. By that time, Powhatan and John Rolfe were dead, and peace with the Indians had been broken in 1622 by a bloody uprising led by Pocahontas’s uncle, Opechancanough.

Although Pocahontas was one of Powhatan’s favorite children, she probably had little influence over her father’s actions toward the English colonists. However, after she married and traveled to England, she was able to bring the Virginia colony to the attention of prominent English men and women.

Text: Nancy Egloff, Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation historian

Illustrations: Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation collection